Are Women Less Able to Fulfill their Fertility Goals?

A Not-Brief Response to Lyman Stone

On Friday, April 30, the Dispatch published a piece I wrote on fertility trends. I argued that a popular rationale offered for government subsidization of parenting was wrong. Advocates of these subsidies often claim, as Senator Josh Hawley put it, that “Over the past several decades it has become increasingly difficult for working- and middle-class parents to afford to raise a family.” I contend that this view is incorrect. If affording to raise a family has become more difficult, we would expect that women today have been less successful than in the past at meeting the fertility targets with which they began adulthood. To the contrary, I showed that millennial women in their mid-30s have been at least as successful as late-boomer women were at the same age to reach the fertility target they had declared when they were young adults.

I plugged my piece with a Twitter thread, in which I took the opportunity to preempt some possible rejoinders to my piece. I knew that Lyman Stone, a demographic researcher with expertise in family and reproductive issues, had written some of the most influential recent studies with which my conclusion was at odds. So I wanted to mention his research and say why I thought my evidence was better. I linked to his work and spent a few tweets offering a critique. (At the time of publication, these links to tweets were, for some reason, redirecting to the top of threads, at least in Chrome. Copying the link after you are redirected and pasting it into the address box seems to work. Don’t use Twitter as your primary research publication method.)

Lyman quickly responded that, “@swinshi is wrong.” Dozens of tweets followed, and by the end, we had exchanged our data files at my suggestion.

So am I wrong? Here I offer up a full response to Lyman. I do so primarily because, as far as the evidence can tell us, my claim about the success of millennial women versus late-boomer women in achieving their desired fertility is correct. Lyman not only failed to refute my analyses, he actually provided additional evidence in support of them. The past analyses of his that he cited confirm that millennial women will be as successful as late-boomer women at achieving their desired fertility. When we shared our data at my urging, his reanalysis using the datasets on which I relied affirmed my findings even as Lyman cast more doubt on them. And my reanalysis of his data uncovers multiple large errors that invalidate his remaining objections.

Since we are debating an important policy question, it is of utmost priority that interested parties not come away from this debate thinking that the answer is muddier than it is. (There is a question about whether or not Gen Z will be as successful, to which I return toward the end of this response.)

Secondarily, I also want to cast a light on Lyman’s Twitter-optimized style of argumentation and why it falls short of the rigor we need in policy debates. Resolving empirical questions calls for respect and humility, for transparency and a willingness to concede points graciously. These debates end up being quite technical, so it is easy for someone to give an incorrect impression to people not trained in empirical methods by confidently making a variety of ephemeral claims over dozens of tweets.

Resolving these policy questions also requires that researchers provide enough information to evaluate their claims, and that they not casually make assertions that turn out not to be true. Lyman is a knowledgeable researcher and skilled analyst. I have long admired his commitment to applying data toward the end of answering policy questions. But in this and other episodes, it has been frustrating to try to pin him down on the details of his analyses.

At one point in his response to me, Lyman opined that, “publishing errors in low-stakes unimportant environments like twitter and then having others find them is preferable to….adopting cumbersome procedures which inhibit review and discussion.” The problem, though, is that Twitter is itself a cumbersome medium for empirical debates, and it is a medium that discourages the provision of methodological details. It is also difficult to adjudicate which points are and are not valid by scrolling through threads. And because Twitter is viewed as lower-stakes than traditional publications, it encourages people to make claims that are not well-supported, which then propagate further than many published studies.

As I will show, Lyman’s tweet downplaying publishing errors came after he had initially ignored my argument, accused me of bad faith, offered his own counter-evidence that ended up supporting mine, wrongly asserted that I was comparing datasets that weren’t consistent with each other, and declared my analyses must be wrong because his results using the same data were different. It came after I provided my data files in response to his accusing me of having coding errors but before he realized, after reviewing my files, that actually he had made errors and, apparently, I had none worth mentioning. It came before he revised his conclusion to say my analyses were actually “fine,” while maintaining incorrectly that because of problems with the data, I was still probably wrong. It also came before he provided me with his data file, in which I discovered multiple errors that Lyman had missed, which I report below.

Don’t cry for me; I’ve seen worse (and have not always been my best self in empirical debates). The point is to get closer to the truth and promote effective ways of doing that. A style of argumentation that combines a cavalier attitude toward accuracy, opacity in the presentation of evidence, an unmerited confidence in the rightness of one’s assertions, and an uncharitable view of other researchers is a harmful style for the goal of improving the lives of families through policy.

An Initial Off-Topic Burst Ends with an Accusation of Bad Faith

Lyman’s initial responses offered no evidence at all about whether the trend I found was correct or about trends in the affordability of raising a family. His thread sprawled over a number of interesting topics unrelated to my claims. Nearly half an hour in, Lyman declared, “folks the idea that financial incentives aren’t effective [at increasing fertility] is wrong. It doesn’t match self-reported [fertility] intentions, and it doesn’t match the empirical literature on such incentives.” But I never argued that financial incentives aren’t effective for increasing fertility.

These tweets culminated with the proclamation that “@swinshi ’s arguments that below-desired fertility is a ‘problem which does not exist,’ or his related argument that marriage is not deterred for financial reasons, or his argument that financial concerns are not a major force suppressing fertility, are all wrong.” But again, none of these are arguments I made. My entire piece is addressing the claim that women are less successful at achieving their desired fertility than in the past — that is the problem that does not exist. (Or if it does, it is a very recent problem that has yet to be reliably demonstrated.)

While ignoring my argument about the trend in achieving desired fertility, Lyman tried to impugn my qualifications as a researcher as a substitute. In the middle of a tangential discursion about how stable fertility preferences are and how predictive they are, Lyman lamented — for the second time at that point — that I “gotta do the lit review.” He claimed that I was unfamiliar with past research in which he had used the same dataset that I used. In reality, that research inspired an email exchange two years ago between Lyman and me that directly led to my idea to look at trends using the dataset. Lyman had not done so, and I thought that was the most direct way to get at the question of whether the ability to achieve desired fertility had changed.

Lyman objected that comparing achieved fertility to expected fertility, as my analyses did, was not the same as comparing achieved fertility to fertility preferences. This was a point I took care to make myself and to address in my research. I showed that the responses to questions about expected fertility and desired fertility were extremely similar in the one survey where I could look at both.

I was surprised that Lyman went to such great effort to rebut arguments that I didn’t make without addressing the argument I did make, but it soon became clear what was going on. Lyman alleged that the entire purpose of my piece was to use a “motte and bailey” rhetorical strategy — to advance a more-controversial and less-defensible claim by making a less-controversial and more-defensible one. Essentially, Lyman accused me of believing that financial issues bear no relationship to the successful achievement of fertility preferences but cynically advancing that belief with a narrower claim about a trend. It was, he said, a “bait and switch.”

An Accidental Affirmation of My Findings

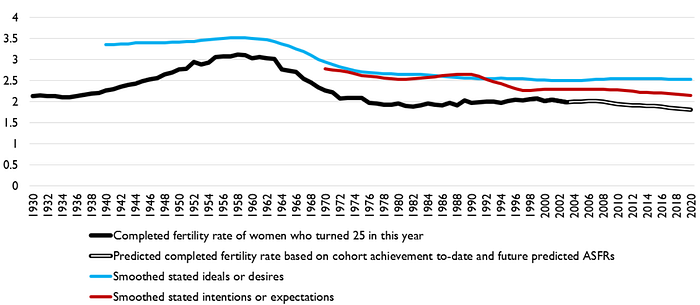

Later, Lyman posted charts ostensibly meant to rebut my conclusion. The charts showed trends in completed fertility, in ideal or desired fertility, and in expected or intended fertility. The gaps between completed fertility and ideal/desired/expected/intended fertility indicate how successful women are at achieving their preferences and how that has changed over time. Here are the trends:

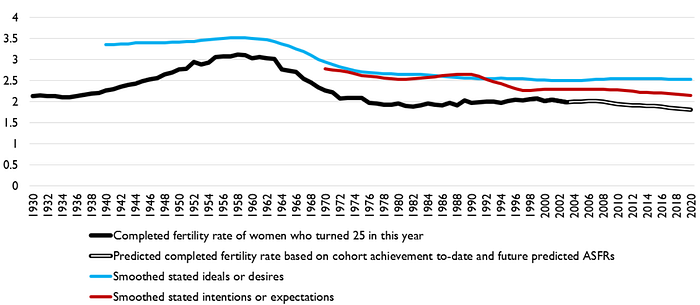

And here is the same information, focused on the gap between completed fertility (the black line in the chart above) and ideal/desired/intended/expected fertility (red and blue lines above):

We can compare his estimates to mine in a fairly straightforward way. Lyman plots completed fertility for a birth cohort at the year in which they turned 25 years old, so the completed fertility he shows for 1980 of around two indicates that the women who were 25 in 1980 (born in 1955) eventually had an average of two children. My late-boomer estimates are for women who were 25 between 1986 and 1989, and the completed fertility estimate in the survey I use matches that shown by Lyman over those years. In my survey data, the late-boomer women wanted an average of 2.6 children when asked in 1979 (when they were 15 to 18 years old) and expected an average of 2.5 children. Lyman’s chart shows that the “ideals or desires” data points over these years and the “intentions or expectations” data points were between 2.5 and 2.6.

We also find similar results for the millennial cohorts I examined. I cannot observe completed fertility for women in the survey I use, age 25 between 2005 and 2008, because they are still in their childbearing years. (Lyman projects their competed fertility.) Nor do I have information on their desired fertility — only their expected fertility. But I find they expected an average of 2.1 children when asked in 2001 (when they were 18 to 21 years old). Based on the estimates in the late-boomer survey, in which women are asked about expected fertility both during this age range and three years earlier), we can assume the expected fertility of the millennials as 15- to 18-year-olds would have been no higher than 2.3 children. Lyman’s chart indicates the expected fertility of these cohorts was around 2.25 children.

Lyman’s own evidence shows that the millennial women in the cohorts I examined will be at least as likely to achieve their desired fertility as late-boomer women. (Compare the 1986–89 levels in his gap-focused chart, above, to the 2005–08 levels.) Actually, the chart doesn’t quite show that, because by the metrics he’s using, some women who exceed their fertility targets balance out women who miss them, so technically, his chart doesn’t directly assess whether it is less common today to successfully have at least as many children as desired.

Lyman apparently did not recognize he was bolstering my case, because he later insisted that my analyses of the survey data I used were flawed. We’ll take a look at that criticism next, but do keep in mind the inconsistency of saying his charts refute my claim using survey data even though they show the same thing, but my analyses using survey data are wrong even though they show the same thing as his charts.

A Series of Invalid Criticisms amidst Confusion about My Analyses

My analyses relied on the “National Longitudinal Survey of Youth” — or rather two different NLSY surveys, one that began in 1979, and one that began in 1997. I’ll refer to these as the NLSY79 and NLSY97 below. I created similar samples using each dataset, looking at the fertility women expected as 18- to 21-year-olds (either 3 or 4 years into the survey) and comparing it to achieved fertility as far into the future as possible (between the ages of 33 and 37). When Lyman turned to addressing my analyses directly, he started with a blizzard of unverified claims and irrelevant objections.

Perhaps most egregiously, Lyman claimed (and said as much here too), “the 1997 expectation question is totally different from the 1979 one,” but that’s not true of the questions I examined. Both surveys asked, “Altogether, how many (more) children do you expect to have?” (See these links.) Lyman apparently thought I was using questions I wasn’t.

Actually, maybe the most egregious claim was when Lyman said of the NLSY97 that only a non-random subset of the participants were asked the expectations question I used, an assertion he continued to make when I expressed skepticism. Eventually, he had to retract that assertion, because the NLSY97 documentation contradicts him — the expectations question was given to about a fourth of the NLSY97 sample, but respondents were randomly assigned to the four groups. Lyman continued to claim (without offering evidence) that the subsample wasn’t representative of women generally. (Later he offered some evidence, but that turned out to be badly flawed, as discussed below.)

When I asked for more information about these claims, Lyman replied, “Look at the data man! Read the codebook!,” as if I have not been using the NLSY data since 2002. He asked how I handled questions that apparently resulted in lots of response errors, but I didn’t use those questions at all. He referred ominously to a “weird expectational probabilities landmine NLSY planted for researchers,” but that too seems to be about questions I didn’t use. He said the relevant survey question was discontinued in later waves because of the low quality of responses it produced, but that, too, appears to be in regard to a question I didn’t use.

He went on about problems with these questions I didn’t use and explained to me why other researchers don’t use these questions I didn’t use. Lyman, in apparent sadness that I could be so naïve, confessed that, “I don’t see why this [information about questions I didn’t use] would be convincing when the vastly larger database of other surveys and vital statistics [referring to his charts that affirmed my results] didn’t convince you.” He also charged, “But look, you will find a reason to disbelieve any data source I find!” and said I was just looking for “ad hoc reasons to disbelieve each piece of evidence.”

A Refutation That Later Turns Out to Be Wrong

Eventually, Lyman put out his own estimates from the NLSY data, purporting to show that mine were wrong. He found that 50 percent of women in the NLSY79 but 60 percent in the NLSY97 failed to achieve their fertility expectations. He would later revise these estimates to 52 percent and 46 percent, after fixing errors, though they would not make an appearance outside the spreadsheet he provided after I suggested we share our data. As should be apparent, these unpublished revised figures affirm my conclusion that millennials have done at least as well as late-boomers achieving their desired fertility.

Before he found his data errors and presented different results to Twitter, Lyman speculated about why I was wrong. He surmised that I had a “coding issue” (translation: I messed up the number-crunching). He wondered if I was missing women who drop out of the datasets because they stop participating or die. But that was because he wrongly guessed that I estimate achieved fertility using the final wave of each dataset, despite my saying otherwise in the Dispatch piece.

As already noted, Lyman also thought the expectations question from the two datasets weren’t directly comparable, but he was entirely wrong. The questions are worded identically in both datasets. He expressed surprise that I’d use a sample of under 1,000 people in the 1997 dataset, though this is well above the thresholds used routinely in social science.

In hopes of resolving the discrepancy between our estimates, I suggested to Lyman that we share our data files. I posted mine on Twitter on Saturday afternoon, and Lyman posted his Monday. But before doing so, he took the opportunity to reanalyze my numbers and publicly cast more doubt on them. My subsequent analysis of his data finds several large errors that render his critique baseless.

Lyman “Gets Closer” to My Numbers

Having examined the data I provided him, Lyman first acknowledged errors in the results he showed earlier. He then announced that with the data I provided he was “able to get closer to @swinshi’s numbers,” and that “it looks like the share [of women] undershooting [their fertility expectations] was approximately stable between the NLS cohorts, not falling as @swinshi’s figures seem to suggest.” His new estimates indicated that 45 to 55 percent of women in the NLSY79 achieved their fertility expectations, versus 52 percent of women in the NLSY97. Here’s his chart:

It turns out that most, but not all, of the estimates in his chart include men, despite the chart’s title. This is important because Lyman’s “1979 cohort, 82 survey” bar is the only one that excludes men (because they were not asked the expectation question in the 1982 survey wave). Had men been included, the bar would have been higher. In my own data, when I exclude men from the 1979 survey wave (the light blue bar in the chart, I find 55 percent of women undershot their expectations by their mid-30s, but if I include men, that goes up to 59 percent. In the data Lyman provided me, if I exclude women from his estimate for the 1979 wave (again, the light blue bar) it drops from 55 percent to 51 percent. All of this is to say that comparing Lyman’s 45 percent figure in the chart above (the dark blue bar) to the 53 percent he shows for the NLSY97 (the red bar) makes it look like fewer women have achieved their fertility expectations over time, but that’s largely because the dark blue bar includes men.

The upshot is that, comparing Lyman’s light blue bar to his red bar (both of which include men), achieved fertility improved over time, as I found.

Lyman’s new chart gave the impression that he was still looking at completed fertility (which, as noted in the legend to the chart, involved guessing at the additional number of children NLSY97 women would have). But the figures in his spreadsheet clearly indicate that the chart no longer looks at completed fertility but achieved fertility as of the years I used in my analyses (1998 and 2017, when my sample — but not his — was 33 to 37 years old).

The completed fertility estimates from his spreadsheet, again ignoring the NLSY79 estimate from 1982 that excludes women, indicate that the change was from 52 percent in the NLSY79 to 46 percent in the NLSY97. These estimates, too, affirm my results. Instead of presenting these estimates, however, with Lyman’s previous method of guessing at the completed fertility of NLSY97 women, he presented different estimates that used a different method of guessing at their completed fertility. That rescued his claim, inconsistent with his fertility-gap charts presented days earlier, that millennials will be less successful achieving their expected fertility than late-boomers.

However, all of these completed fertility analyses suffer from an error I later found in Lyman’s spreadsheet. In the NLSY79, he looks at variables indicating the number of children ever born in each survey between 1994 and 2018, as well as a variable that indicates the number of children ever born for every woman in the survey regardless of if or when they drop out of the survey. For women who drop out, Lyman is understating the completed fertility of some of them, because he takes the number of children they have ever had as of, say, 1994 and keeps them in the data, whereas some of these women drop out of the survey after 1994 and have additional children we don’t ever see. Indeed, some of them drop out in 1980, but Lyman still counts up any children they’ve had by then and calls it their “completed fertility.” That will increase the number of women who “fail” to achieve the fertility they expected in 1979, even though some of them eventually succeeded after they stopped participating in the survey.

In the NLSY97, it appears that Lyman has a similar issue in that he takes the maximum number of children ever born as of any survey wave between 1997 and 2017. If someone drops out of the NLSY97 after 2002, their achieved fertility will compare the expectation they expressed in the 2001 wave with the number of children they had had as of 2002. Again, many of the women who drop out will eventually achieve their fertility, but we won’t see it in the data; instead, they will look like they failed to achieve their fertility.

While trying to show that the data said the opposite of what I claimed, Lyman also repeated his view that the data are incomparable, because “The respondents were surveyed with different questions at different times and selection into being questioned was not evenly distributed [with respect to] variables of interest.” This selection issue requires more explanation, but before getting to that let me reiterate that I specifically chose the samples and variables I did so that respondents were asked the same question at the same ages.

The comparability issue Lyman spent the most time on was the question of whether the women who answered fertility expectation questions are representative of women generally, particularly in the NLSY97. Lyman showed charts indicating that women who had two or more children in 2001 were more likely to have received the fertility expectation question than women who had one child, who were more likely to have received the question than women with no children.

But Lyman uses unweighted data that don’t account for the oversampling of nonwhites. (More on this below.) Correcting that error reveals that women who had no children and women who had one child in 2001 were essentially equally likely to receive the expectations question. Women who had two or more children were apparently more likely, but this is a very small group — under 4 percent of the women — so the figure is imprecise. When I tested the differences between these three groups (no children, one child, two or more) using Lyman’s data, they’re not statistically significant, meaning they’re not meaningful.

Meanwhile, Lyman shows a declining likelihood of receiving the expectations question in the NLSY79 as the number of children increases. But that conclusion is based on an egregious coding mistake in his spreadsheet. He’s actually showing something like the share of people who do not receive the 1982 expectations question out of those who do receive the 1979 expectations question, not the share of people who receive the 1982 expectations question out the share who might have. He finds that large shares who received the 1979 question did not receive the 1982 questions, but that is largely because he includes men, who received the 1979 expectations question but not the 1982 one. This is an egregious error.

Lyman ended his brief by again suggesting that analyses of over 2,000 NLSY79 women and over 650 NLSY97 women relied on samples that were too small and that the questions asked in the two surveys weren’t sufficiently comparable, even though they are exactly the same. He also rattled off a bunch of rejoinders to the arguments raised the previous week that I never made but that he suspects I believe.

More Problems Emerge

When I dove into the spreadsheet that Lyman provided so that I could assess his results, I found some pretty big problems, several of which I’ve already described above. A few more are worth emphasizing before we leave the NLSY discussion behind, with my conclusion intact.

Lyman incorrectly used “sample weights” in his analyses. Weights are used to inflate the number of people represented by an individual person in the data. This is necessary because we care about the actual population of real-world people rather than the specific sample of people in the data who are supposed to stand in for them. Sometimes certain kinds of people are over- or under-represented in datasets. Often, that’s on purpose, such as when a survey includes an “oversample” of racial minorities in order to ensure there are enough for analyses by race. If you don’t down-weight individual minority respondents when you look at the whole sample, then you end up producing results that don’t accurately depict the overall population.

Lyman uses weight variables that produce nationally representative results when the oversamples of low-income whites and of blacks and Latinos (and a smaller military sample) are included in NLSY79 analyses and when oversamples of blacks and Latinos are included in the NLSY97 analyses. But he excludes those oversamples from his analyses, so his samples over-weight the experiences of whites. (The remaining nonwhites have weights that down-weight their prevalence in the population, because there are supposed to be so many more in the oversamples.)

Using the proper weights, whites in the NLSY79 are 80 percent of the population in 1979. But excluding the oversamples (as Lyman does) and using the weight variable appropriate only when they are included (as Lyman does), whites are 93 percent of the population. Similarly, in Lyman’s NLSY97 analyses, whites are 71 percent of the population in 1997 using the weights and correctly including the oversamples but 81 percent when using weights but improperly excluding the oversamples.

My own analyses include the oversamples and use the proper weight to make the results nationally representative. It is interesting that the results Lyman showed before he received my data and discovered his coding errors used the oversamples, while his new results do not. Lyman had even gone so far as to invoke Sir Mix-A-Lot in declaring his love of “big SAMPLE SIZES.” But then he dropped the oversamples.

Another difference is that while Lyman uses (the wrong) weights from the 1979 wave of the NLSY79 (the start of the survey), and weights from the 2001 wave of the NLSY97 (but incorrectly), I use weights from 1998 and 2017, the years in which I observe middle-age fertility. By doing so, I ensure the weights I’m using account for “differential sample attrition” — the unequal rates at which certain people drop out of the survey over time. People can drop out due to death or because they stop participating. If you use the 1979 weights (even the correct ones) to look at outcomes in 1998, your results will disproportionately reflect the experiences of people who are less likely to leave the survey between 1979 and 1998.

Imagine all black respondents but one left the survey after 1979, but you used her 1979 weight to represent all blacks. Your results would heavily reflect the experiences of whites. But using the 1998 weight would inflate the number of people represented by the remaining black respondent as best is possible. Adjusting for attrition is a crude methodology, because, for instance, the black people who do not drop out of the survey are probably different in unobserved ways from the black people who do drop out. Weights only adjust for attrition along a few observable demographic lines. But adjusting for attrition roughly is better than not adjusting at all. Lyman’s choice means he is making no adjustment at all.

The same argument holds for the NLSY97 (though Lyman uses the 2001 weights there rather than the 1997 weights, which would be consistent with his using the weights from the start of the survey in the NLSY79).

Another difference between our analyses is that Lyman includes all eight birth cohorts in the NLSY79 and all five in the NLSY97, while I narrow both to four cohorts to keep the analyses consistent in terms of the women’s ages. In the NLSY97, the five cohorts range in age from 17 to 21 at the end of 2001, the year fertility expectation questions were asked. NLSY79 youth were asked these questions in 1982, at the end of which they were 18 to 25. Therefore, I look at four cohorts from each survey, ages 18 to 21 when they were asked about their fertility expectations.

My approach also has the benefit of dropping older cohorts in the NLSY79 who, by 1982 were ages 22 to 25 and sometimes well into their childbearing, which could have affected their responses to the expectations question. In particular, if affordability problems affect expected or desired fertility, we might be concerned that the preferences of women at, say, age 25 would already have been affected by these problems. That would weaken the ability of my analyses to say anything about whether affordability concerns have become more important — especially because no 25-year-olds answer the expectation question in the NLSY97. For purposes of trend analyses, it is important to keep the 1979 and 1997 samples consistent in terms of when we observe their achieved fertility as well as when we assess their expected fertility. Lyman’s approach fails to do that.

Lyman also looks at NLSY79 responses to an expectation question asked in 1979, three years before the 1982 wave. The women he considers here, though, are as young as 14 years old, again younger than anyone who receives the expectation question in the NLSY97. Further, by 2001, some women have dropped out of the NLSY97 — another reason to use the 1982 expectation data in the NLSY79 for consistency, since no one will have dropped out of the NLSY79 in 1979 (the first year it was administered).

Do My Analyses Miss A More Recent Deterioration in Achieved Fertility?

Before drawing this to a close, I want to return to the trend charts that Lyman presented before he dove into the NLSY analyses. Those charts do show a decline in achieved fertility for more recent birth cohorts (roughly from those born 1975 to those born 1995). For women born after 1985, his chart suggests that achieved fertility will be worse than for my late-boomer cohorts (though no worse than for earlier boomer cohorts). Since my millennial cohorts were born between 1980 and 1983, perhaps my analyses were correct but were unable to identify the more recent deterioration?

While Lyman’s estimates of women’s ability to achieve desired fertility align closely with mine for the cohorts I analyzed, there are good reasons to doubt that the gap between preferences and achieved fertility has really widened in recent years.

Lyman’s trend in completed fertility is the most reliable, as it may be more or less directly observed in surveys that include women who are no longer of childbearing age. However, recent cohorts of women are still in their childbearing years. That means that Lyman has to project their completed fertility, by assuming that the future fertility of younger women when they are older will look like the fertility of older women today.

Lyman protested to me that this is a straightforward calculation. That may be, but his projections need not be off by much to affect his trends in fertility gaps. His chart shows that the gap between ideal/desired fertility and completed fertility grows by 0.2 children for recent cohorts. The gap between expected/intended fertility and completed fertility grows by more like 0.15 children.

It’s one thing to look at women born in 1980, observe their fertility through age 40, and then make assumptions about how many more children they will have. So his data point for 2005 (which is where he plots the completed fertility of women born in 1980, since they were 25 years old that year) is surely a quite accurate projection. But women born in 1995 were only 25 in 2020. Lyman projects how many children they will have in the next two decades based on today’s women aged 26 and up. He doesn’t offer a sensitivity analysis to let us know how much his projection for them might be off.

And then his fertility gap estimates are created by subtracting ideal/desired fertility or intended/expected fertility from completed fertility. Where do these lines come from? You have to have read Lyman’s earlier work to figure this out, but they are based on estimates taken from a variety of sources. When sources yield different estimates for the same year, Lyman combines them (how, we don’t know) into a single data point for each year. Compare the blue line in the chart he posted to Twitter…

…to the underlying estimates he displays in an earlier piece:

Three points are worth making about the earlier chart with the disaggregated trends. First, Lyman’s “ideal/desired” line combines estimates of the general ideals women have about the best number of children to have and estimates of personal ideals (the number of children women desire to have themselves, personally). Where we can compare trends and levels for general ideals and personal ideals, they sometimes are inconsistent by enough that how these estimates are combined can make a difference to the trend. Compare the pink and purple lines in the disaggregated chart and it appears that general ideal fertility fell more than personal desired fertility, and the former was lower than the latter by 0.2 in the most recent year both can be compared. In contrast, comparing the orange and red dots near 1980, this second data source found that personal desires were lower than general ideals by about 0.4. During the 1970s, did “ideal/desired” fertility rise, as suggested by the “ideal” data points, or did it fall, as suggested by the “desired” data points?

Second, most of the estimates — and all of the estimates for recent years in which Lyman shows widening fertility gaps — are based on general ideals, not on personal desires.

Third, even general ideal estimates from different surveys sometimes produce results that differ by an amount as large as the recent increase in the fertility gap that Lyman reports. The “NSFG” estimates in the chart are regularly 0.2 higher than the Gallup and “GSS” estimates, for instance.

What else don’t we know about Lyman’s methods? We don’t know anything about the populations represented by the underlying estimates that get smoothed. The estimates presumably all come from nationally representative samples, and it looks like they are confined to women. But what age ranges do they represent? We don’t know because Lyman doesn’t say. All he says (in the subtitle of his latest chart) is that his estimates are for “reproductive-age women weighted equivalents,” which tells us very little.

Lyman wants us to take the gap between completed (later) fertility of 25-year-olds in 2000 and the 2000 desired fertility in his chart as reflecting the unachieved fertility levels of women 25 years old in 2000. If the 2000 desired fertility levels are based on 25-year-old women, we might have confidence in the gap he estimates. We should have much bigger concerns if the 2000 desired fertility levels are based on women 18 to 44. That mixes the fertility desires of 27 birth cohorts and compares them to the completed fertility of one.

The estimates are also smoothed in some way that Lyman doesn’t explain, meaning that year-to-year fluctuations are displayed as smaller than they really are.

So in the end, we have Lyman saying that the gap between completed fertility and fertility preferences has widened for women born after 1975. He says so based on projections of completed fertility for women who are increasingly early in their childbearing years and, it appears, based on survey evidence of general ideals about the best number of children to have (rather than the number of children women say they personally want to have) for women of widely varying ages.

Lyman may eventually be proved right, but if he wants to persuade anyone not already inclined to agree with him, he will need to provide more details regarding his analyses and more sensitivity checks. Even if his chart ultimately is vindicated, then that would indicate that while my piece was correct that millennials have been no less successful than late-boomers at achieving their desired fertility, Gen Z women will be less successful. And the chart indicates that not only millennials and Gen Z but boomers have been less successful than Gen X at achieving desired fertility.

Research has to be conducted rigorously and with the aim of getting at the truth. It is never fun to have to defend empirical claims. In the best-case scenario, you’re right but you create an uncomfortable situation. In the worst-case scenario, you discover you’re wrong. But regardless, the important point is for researchers to get incrementally closer to the truth. This is a project to which everyone in the policy research community contributes. The point is not to build brands or police mavericks; it should never be personal. I will retract anything here that turns out to be incorrect, but I expect other researchers to be equally committed to spreading reliable, factual information in the interest of improving people’s lives by addressing their problems effectively. There are better and worse ways to do that.